Written by Bréyon Austin, Clinic and Pro Bono Coordinator

Please Note: the below contains images and content that might be upsetting.

Anxiety and fear, the only emotions I am able to name as the flight from San Francisco touches down in Montgomery. My first trip to the deep south, to the land that has represented oppression, death, inequity and loss, to the land of my people. The land contains the sweat my ancestors shed while working those cotton fields. The land contains the blood my ancestors shed while being whipped and lynched. The land represents all that has been and all that will come.

As the pro bono coordinator of LCCR’s GLIDE Unconditional Legal Clinic, I had the opportunity to join GLIDE staff and community members on a pilgrimage to Montgomery, Alabama. Together we explored key sites instrumental to the Civil Rights Movement, past and present.

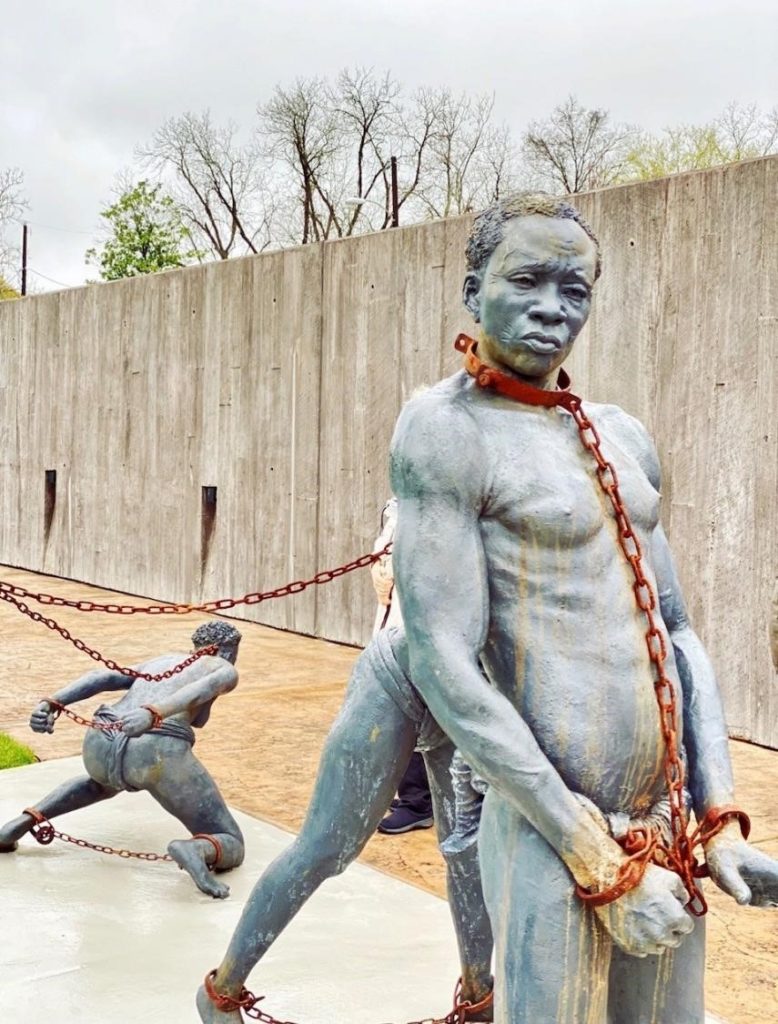

The Equal Justice Initiative’s (EJI) Legacy Museum makes these connections explicit. Housed on the site of a former warehouse used to hold enslaved Black people, the museum traces the history of enslavement from chattel slavery to the “Black Codes” and convict leasing to mass incarceration today. Walking into a warehouse that once held Black people captive as they awaited auction was soul shaking. The tears flowed from the moment I stepped foot onto that hallowed land knowing I stood where people who looked like me were terrorized because of the color of their skin. Knowing people who look like me are still terrorized today because of the color of their skin.

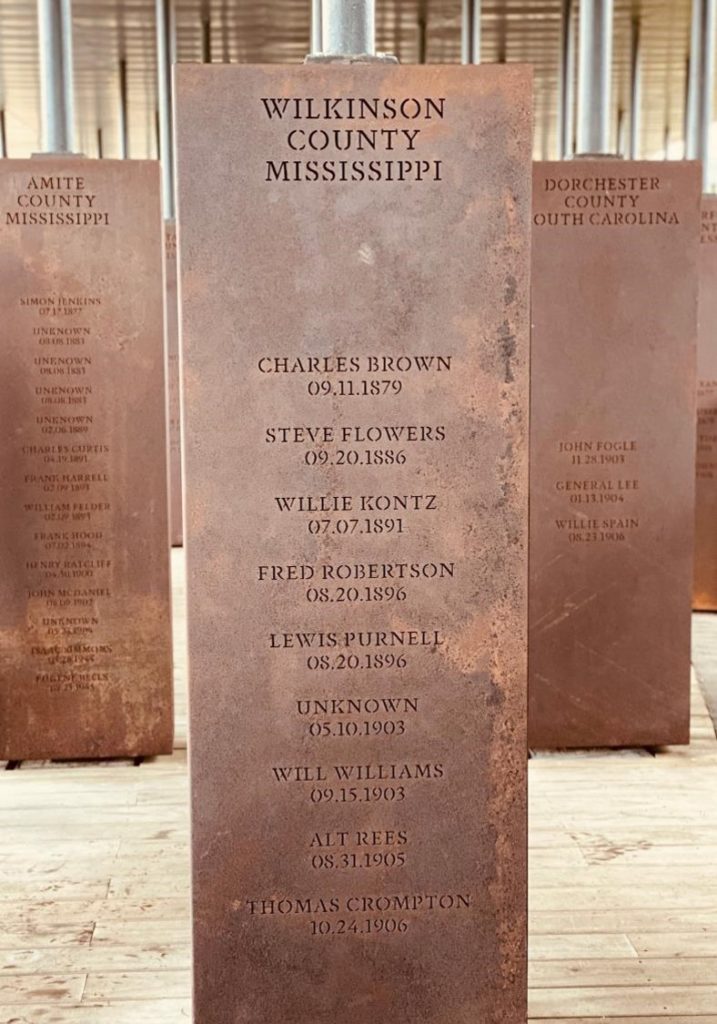

My fears are rooted deeply in my sense of identity that its near impossible to determine where the fear ends and where I begin. Growing up as a queer Black woman the south never seemed a safe place to visit and that sentiment remains to this day. Our next stop was to EJI’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which commemorates the more than 4,400 African Americans murdered in racial terror lynchings in the United States (U.S.). This memorial, the first in the country, paints a haunting accounting of those killed due to government-sanctioned racism in this country between 1877 — the end of Reconstruction — and 1950. Standing amongst the columns listing the names and dates of those lynched solely for being Black in a land that balked at the idea of equity shifted the reality of my anxiety from the theoretical to the tangible. This awareness would have been painfully powerful even if these types of killing were solely relegated to the past, the unfortunate truth is terror lynchings never ended. Racial terror continues to be seen today as evidenced by the number of people of color killed by the police in the U.S. today.

We had a chance to hear from two former EJI clients who have been directly impacted by the prison-industrial complex. Anthony Ray Hinton spent 30 years on Alabama’s death row for a crime he did not commit before EJI founder and civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson took his case to the Supreme Court. Hinton’s tearful declaration still echoes in my ears, inspiring me to continue the fight for justice. “All I want is an apology from someone in power, an acknowledgement of what I went through,” he told us. “I have been out of prison for five years and no one has apologized to me.”

Kuntrell Jackson, one of the petitioners in Miller v. Alabama (2012), spoke about serving nearly 17 years in prison after being sentenced to life at just 14 years old. Jackson discussed his new outlook on life after the Supreme Court’s finding that the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment forbids the mandatory sentencing of life in prison without the possibility of parole for juvenile offenders.

“But the question becomes what are you going to do with your life?” he said. “You going to stay mad, dwell on what happened, harm somebody? Or you going to let your anger spark something inside of you and make you do something to change it?”

We spent our last morning in Montgomery taking in the sights of the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) and their Civil Rights Memorial. While there we had the great opportunity to hear from Joe Levin, Co-Founder of the SPLC. Levin spoke of his journey from being raised with racist beliefs in Alabama to teaming up with the legendary civil rights and SPLC attorney Morris Dees to fight for desegregation, integration and prison reform. His message about his transformation from racist to freedom fighter is one that needs to be heard today, especially given these decisive times.

We started and ended our pilgrimage at the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Legacy Center, where Dr. King delivered his first sermons. From the bus boycotts, to the marches, protests, demonstrations and the development of a law center focused on righting the wrongs done to and against Black people, Montgomery is the land of the people who wouldn’t let their fear, anger and anxiety stop them from fighting for freedom. I bring that fire back with me to the Bay Area. This powerful experience left me humbled by the sacrifice of those who have fought and died for freedom, equality, and justice. I felt encouraged by our work at LCCR to fight back against systems of oppression, assist clients in self-advocacy, and partner with Pro Bono volunteers committed to challenging racial and economic barriers to equal justice. I am going to take Kuntrell’s advice and let my anger become my motivation.

Moving forward after this experience is both exhilarating and daunting. As Ella Baker said, “We who believe in freedom cannot rest…” There is so much to do to keep fighting injustice and I feel rateful that my job allows me to make an impact. I have the great opportunity to host our GLIDE Unconditional Legal Clinic (Legal Clinic) which takes place twice a week on Mondays and Thursdays in San Francisco’s Tenderloin District. Many of our clients are people of color who have had negative interactions with members of law enforcement. Our Pro Bono volunteers have heard stories similar to those told on the walls of the EJI museum. Many clients arrive at the Legal Clinic seeking assistance and information about how to respond to instances of police misconduct, including brutality.

Our group of over 100 was comprised of members of GLIDE staff, University of California San Francisco personnel, San Francisco Police Department, and various other community organizations. The organizers were very intentional when choosing the participants, those of us selected are in helping professions. We made this journey in order to better educate ourselves about racial inequity as it pertains to our fields. I sat in conversations with doctors and police officers who expressed concern and excitement about how to incorporate what they have seen and learned into the work they do.

This is a journey we are all in together-clients, helpers, professionals, donors, politicians, etc. We all must do our part. Now.