East Bay Express: Chief Justice Seeks Emergency Traffic Court Reform, Jerry Brown Pushes Amnesty Program

Original article appeared in the East Bay Express.

by sam levin

Traffic courts throughout California trap people in poverty with exorbitant fines and harsh policies that can make it very challenging for low-income people to resolve minor infractions — a problem I explored in-depth in a recent feature story, “The High Cost of Driving While Poor.” In the wake of increased media scrutiny tied to a damning report on traffic fines — co-authored by the East Bay Community Law Center and other California legal aid groups — state officials have proposed a number of solutions aimed at tackling some of the inequities of this legal system.

Last week, California Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye announced that she is pushing for an “emergency action” that would help address one of the central concerns of critics — that the court system is often inaccessible to people who can’t pay expensive fines upfront. Cantil-Sakauye’s efforts come as Governor Jerry Brown, in his latest budget proposal, has continued his push for a so-called “amnesty program” that would reduce the amount of outstanding traffic court debts for some defendants.

These new efforts reflect an increasing acknowledgment throughout state government that the current system of traffic fines is often unfairly harsh and disproportionately impacts low-income residents and people of color. As I outlined in my feature story, California over the years has increasingly relied on court fines and fees to raise revenues for courthouses and other government agencies, such that a relatively minor traffic offense that once cost $100 now costs roughly $500. And when people fail to pay the fees on time or miss a deadline to appear in court for a traffic infraction, judges typically issue “civil assessments” which carry additional $300 fines and result in the defendant having his or her driver’s license suspended.

When the courts issue these assessments, they regularly block defendants from having a court hearing on their alleged infractions until they’ve paid the full bail they owe. That means low-income people who miss a single court deadline — including people who are innocent (a victim of identity theft, for example) — can’t even explain their circumstances to a judge until they’ve paid hundreds of dollars.

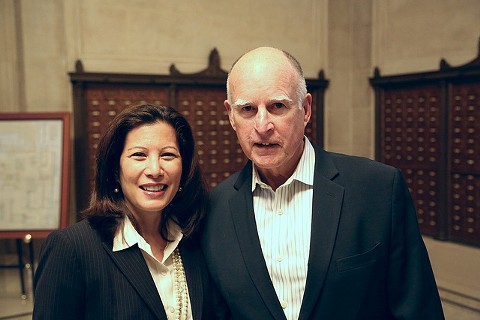

California Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye and Governor Jerry Brown.

It’s the issue of inaccessibility that Cantil-Sakauye aims to address through an emergency action. The chief justice announced last week that she has asked the Judicial Council, the policymaking body of the California courts, to “take emergency action to adopt a rule of court to facilitate access to justice for court users challenging traffic fines,” according to a press release from the council. She said in a statement:

Many of the procedures and practices regarding traffic fines derive from statute. However, the law is confusing and may result in inconsistent practices or policies throughout the state. I’m charging the Judicial Council as the constitutional statewide policymaking body to expeditiously initiate our rule-making process to act on an emergency basis. We need a court rule that makes it clear that Californians do not have to pay for a traffic infraction before being able to appear in court.

One of the criticisms of legal aid organizations is that although judges and commissioners in traffic court have wide discretion to be lenient in the fines they order based on people’s inability to pay, in practice they often issue the harshest punishments allowed.

In their recent report, “Not Just a Ferguson Problem: How Traffic Courts Drive Inequality in California,” advocates argued that traffic court in California has effectively become a two-tired system where people are denied hearings due to their inability to pay fines. In interviews, Alameda County court officials repeatedly argued that the activists are overstating this problem and that local defendants can schedule hearings regardless of their ability to pay. But lawyers with the East Bay Community Law Center — who assist low-income people with their traffic tickets — told me that most people they represent who have missed an Alameda County Traffic Court deadline are automatically barred from having a hearing until they post their full bail. At that point, the county sends their debts to a private debt collection company, and without the advocacy efforts of attorneys from the center or other nonprofits, there is very little these defendants can do to get a trial before paying the owed fines, according to the defense attorneys.

A new statewide rule could help resolve this dispute in Alameda County by setting a consistent rule ensuring people have an opportunity to see a judge, though the specifics remain to be seen.

In an April report to the Judicial Council, Cantil-Sakauye also expressed concerns about the role of fines and fees in courts, noting that in a “pay to play” system, people can be denied access to justice. In the announcement last week, the Judicial Council further noted that the Commission on the Future of California’s Court System — a group charged with evaluating the long-term efficiency and stability of the judicial branch in California — is conducting a broader review of public access to courts (including traffic court) and the impact of fines, fees, and penalties.

Meanwhile, Brown’s amnesty program — detailed in the revised 2015-16 budget proposal released this month (page 51-52 here) — could provide some relief for people currently saddled with old traffic fine debts. Brown has proposed an eighteen-month amnesty program that would allow people with traffic court debt that they owed before January 1, 2013 to pay half of the amount owed. Notably, the program would also allow individuals with suspended driver’s licenses — due to failure to appear or pay in traffic court — to reinstate their licenses. These individuals could either agree to make one payment or sign up for a payment plan. The program would also reduce the $300 court-imposed civil assessment fees to a $50 “administrative fee” for the courts.

The governor’s office estimates that the amnesty program would generate $150 million.

Brown recently acknowledged the incredible struggles traffic court defendants face, saying, “It’s a hellhole of desperation and I think this amnesty can be a very good thing to both bring in money, to give people a chance to kind of pay at a discount.”

While advocates have praised efforts to make this process fairer, many have argued that long-term, systemic changes are necessary. Advocates, for example, have argued that courts should stop suspending licenses for infractions that have no public safety threat; one recent Change.org petition making this argument has more than 6,000 signatures. Some have also suggested that the state should dramatically reform how it generates revenues so that government agencies are not so dependent on fines and fees for minor offenses — and so that judges are not incentivized to inflict the highest fines state statute allows.