CNBC: Wealthier drivers get more tickets, but don't pay

Original article from CNBC

By Mark Fahey

Wealthy drivers may be speeding and running stop signs, but they’re not paying extra for their tickets.

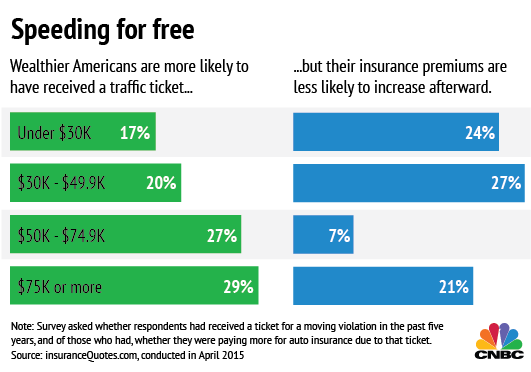

Twenty-nine percent of Americans with incomes of $75,000 or higher report receiving a moving violation ticket in the last five years, but only 21 percent of those drivers saw an increase in their insurance premiums, according to new survey data from insuranceQuotes.com,

People with incomes under $50,000, on the other hand, were less likely to get a ticket and more likely to see their premiums jump.

Twenty-nine percent of Americans with incomes of $75,000 or higher report receiving a moving violation ticket in the last five years, but only 21 percent of those drivers saw an increase in their insurance premiums, according to new survey data from insuranceQuotes.com,

People with incomes under $50,000, on the other hand, were less likely to get a ticket and more likely to see their premiums jump.

There are many reasons why richer Americans may get more tickets, said Laura Adams, senior analyst at insuranceQuotes.com. They could have faster cars, or maybe they’re on the road more, or maybe they just care less about tickets.

“It makes me wonder if the higher-income people are willing to take more risk because they know they can afford it,” said Adams. “If you don’t have any money in savings, maybe you’re less likely to speed to work.”

But why aren’t insurance companies adjusting rates for all those tickets as they happen?

It’s because it costs money to pull all those driving records, said Adams, and insurance companies will request records less frequently for drivers it judges to be less risky. If a person fits the profile of a safer driver, they may not pull records for three to five years, she said.

Age differences may account for some of the difference between income groups, because older people have their records pulled less frequently and richer people tend to be older. Age and gender are important factors insurance companies use to determine risk.

“They’re getting the most tickets, but they’re not getting the rate increase probably just because they’re getting away with it,” said Adams. “They’re just not being scrutinized as much as the lower-income group.”

Richer people may also tend to have better credit, which insurance companies sometimes use to determine how risky a particular driver may be. They also may be more likely to pay more upfront for insurance with better features, like programs that forgive the first ticket or accident.

Whatever the reason, it wasn’t the case when insuranceQuotes.com surveyed drivers two years ago.

In 2013, 36 percent of respondents in the two highest brackets reported premium increases after getting a ticket. Now it’s 7 percent for the $50,000 to $74,900 bracket and 21 percent for the top bracket.

For $30,000 to $49,900, the percent seeing a jump in rates actually increased 9 percentage points, which suggests that insurance companies are pulling those drivers’ records more frequently.

“With insurance companies it’s all about the drivers,” said Adams. “If the profile of a driver is riskier or more expensive as a customer, they’re going to raise rates for that customer to compensate for that risk.”

Traffic tickets can be a major source of revenue for struggling communities, but they can also be a tremendous burden for poorer citizens. The government of Ferguson, Missouri, has been criticized for relying on traffic violations for 14 percent of its revenue, and collecting 44 percent more in total fines and fees than it did only three years ago.

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights of the San Francisco Bay Area released a similar report last week, accusing California’s courts system of preying on low-income citizens to collect billions in debt. An offender’s driver’s license is often kept as collateral until the debt is paid, making it more difficult for poor drivers to get back on their feet.

Insurance rate hikes could have the same effect by making driving prohibitively expensive for people who are already having trouble making ends meet.

“It makes me wonder if the higher-income people are willing to take more risk because they know they can afford it,” said Adams. “If you don’t have any money in savings, maybe you’re less likely to speed to work.”

But why aren’t insurance companies adjusting rates for all those tickets as they happen?

It’s because it costs money to pull all those driving records, said Adams, and insurance companies will request records less frequently for drivers it judges to be less risky. If a person fits the profile of a safer driver, they may not pull records for three to five years, she said.

Age differences may account for some of the difference between income groups, because older people have their records pulled less frequently and richer people tend to be older. Age and gender are important factors insurance companies use to determine risk.

“They’re getting the most tickets, but they’re not getting the rate increase probably just because they’re getting away with it,” said Adams. “They’re just not being scrutinized as much as the lower-income group.”

Richer people may also tend to have better credit, which insurance companies sometimes use to determine how risky a particular driver may be. They also may be more likely to pay more upfront for insurance with better features, like programs that forgive the first ticket or accident.

Whatever the reason, it wasn’t the case when insuranceQuotes.com surveyed drivers two years ago.

In 2013, 36 percent of respondents in the two highest brackets reported premium increases after getting a ticket. Now it’s 7 percent for the $50,000 to $74,900 bracket and 21 percent for the top bracket.

For $30,000 to $49,900, the percent seeing a jump in rates actually increased 9 percentage points, which suggests that insurance companies are pulling those drivers’ records more frequently.

“With insurance companies it’s all about the drivers,” said Adams. “If the profile of a driver is riskier or more expensive as a customer, they’re going to raise rates for that customer to compensate for that risk.”

Traffic tickets can be a major source of revenue for struggling communities, but they can also be a tremendous burden for poorer citizens. The government of Ferguson, Missouri, has been criticized for relying on traffic violations for 14 percent of its revenue, and collecting 44 percent more in total fines and fees than it did only three years ago.

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights of the San Francisco Bay Area released a similar report last week, accusing California’s courts system of preying on low-income citizens to collect billions in debt. An offender’s driver’s license is often kept as collateral until the debt is paid, making it more difficult for poor drivers to get back on their feet.

Insurance rate hikes could have the same effect by making driving prohibitively expensive for people who are already having trouble making ends meet.